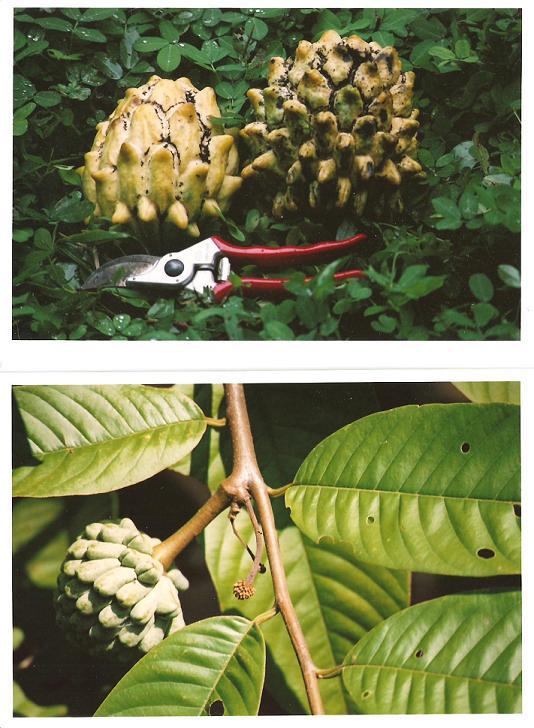

Pili nut is one of the best tasting nuts in the world in my opinion. I encountered my first mature tree at Summit botanic garden, boarding Soberania National Park outside Panama City. The tree has strong structure, very attractive, producing an abundance of nuts. The nuts have a very strong shell containing one elongated kernal.

ORIGIN AND DISTRIBUTION

The Pili nut originates in the Philippines and is widely cultivated both there and in neighboring islands. It can be found in cultivation in Indonesia and Malaysia. The Pili nut has also been introduced into the American tropics where it is produced at a commercial level.

USES AND ETHNOBOTANY

The nut is edible raw or cooked and has a flavor comparable to Mediterranean almond. It can be eaten raw or toasted and can be used to extract an edible oil.

PROPAGATION, CULTIVATION AND MANAGEMENT

Pili nut is a species from the humid tropics, and is best planted from sea level up to 500 meters. The tree prefers deep well drained soils.

Pili nut is a fast growing tree, producing nuts year round. An adult tree can produce around 35 kilos of nuts a year.

The pili tree is excellent for landscaping, as a windbreak, and for agroforestation. The young shoot is edible and the resin-rich wood makes excellent firewood. The green pulp can be made into pickle, while the ripe pulp is edible after boil-ing. It also contains an oil that may be used for lighting, cooking and in the manufacture of soap and other industrial products. The shell makes an excellent cooking fuel and can be made into attractive ornaments. The kernel is edible raw, roasted, fried or sugar-coated, and is also used in making cakes, puddings and ice cream. It is rich in oil, which is suitable for culinary use.

The kernel contains 12-16% protein, 69-77% fats and 3- 4% carbohydrates. It is also rich in minerals, but poor in vitamins. The kernel oil has 60% oleic glycerides and 38% palmitic glycerides.

Pilinut pulp is also edible, containing 8% protein, 37% fats, 46% carbohydrates, 3% crude fibre and 9% ash. The pulp oil contains 57% oleic glycerides, 14% linoleic glycerides and 29% saturated fats.